(Being text of an address by the Chairman, Independent National

Electoral Commission (INEC), Professor Attahiru Jega, OFR, at a Press

Conference on Friday, November 22, 2013)

The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) conducted the

Anambra State gubernatorial election on November 16, 2013. In preparing

for the election, INEC was determined to make it the best election we

have conducted so far, and we prepared for that election adequately – in

terms of operational preparations – more than we have done in preparing

for previous elections.

There were, however, many matters arising from the conduct of that

election. And there is no doubt that INEC’s operational performance in

that election has not met with the expectation of Nigerians of it being

the best election ever conducted by the Commission. We regret failing

the expectation of Nigerians, but we did our best under very difficult

circumstances to have a free, fair and credible election. Nigerians are

also no doubt aware that the Returning Officer, when announcing the

results from that election, declared it inconclusive and mentioned the

need to do a supplementary election in order to conclude the compilation

of results and make a final return.

Basis for Supplementary Election

We have since received complaints from candidates, political parties

and many other Nigerians raising issues with the conduct of the

governorship election. Some have made arguments for outright

cancellation of the election. But we in INEC have held a meeting with

all the field officers – senior management level field officials who

participated in that election. We reviewed the conduct of the election.

We received information about what was done right and where there were

lapses in the conduct of the election. And the Commission met today

(Nov. 22, 2013) and took a decision with regard to the next line of

action.

We regret that in spite of our intention, the Anambra election did

not turn out to be the best election that the Commission has conducted

so far. We regret the challenges we faced in the conduct of this

election. But in our assessment, there is no decision we as a Commission

can take or respect other than the declaration by the Returning Officer

that we should conduct a supplementary election in those areas where

results were cancelled before a final return is made.

We have examined all the accusations and allegations that have been

made, and we came to the conclusion that in spite of minor challenges –

unfortunate challenges in the field – there is no substantial evidence

to support outright cancellation of the process. We believe that

although the Anambra election was not the best election as we had hoped,

there was substantial compliance with the Electoral Act 2010, as

Amended, in the conduct of the election; and that a substantial majority

of complaints that have been laid cannot be substantiated. Therefore,

we have decided that the supplementary election will hold in Anambra

State on Saturday, November 30th, 2013.

Issues from November 16 Election

There is no doubt that there was late commencement of the November 16

election in some polling units, and there is no doubt that this late

commencement resulted from delay in the deployment of election

officials. But where personnel and materials arrived late and it became

necessary to adjust the time of commencement and closing of

accreditation as well as voting, we did so and elections took place

peacefully and successfully.

There were many allegations either by parties or candidates with

regard to the Register of Voters. I want to say that we have

investigated these allegations. Regarding the major allegation that has

been made, which is that the register INEC gave political parties 30

days before the election was different from the register we gave on the

day of the Stakeholders’ Meeting three days to the election: this is not

correct.

We have reviewed the register and we are satisfied that the register

we gave 30 days before the election, and the register we gave out during

the Stakeholders’ Meeting are the same. The only difference is the age

(of registrants), which we explained to the stakeholders and which all

the stakeholders there did not complain about. They understood our

explanation, they were satisfied with it and there was no challenge at

all. So, to now talk about challenges with the register and particularly

to accuse INEC of giving a different register, frankly, is not being

fair to INEC. If anybody or any political party has the evidence of

discrepancy or variance in the two registers that we have given them,

they should come out and prove it. As far as we are concerned, the only

difference between the two registers was the correction of the age; and

this was discussed at the stakeholders’ meeting and they accepted it.

Therefore, the Register of Voters we conducted the election with was the

same register in all material particular, except for the correction in

age on the one that was given to the parties 30 days before the

election.

There were also many allegations of disenfranchisement. This is

regrettable given the energy and attention that INEC has deployed in the

cleaning up of the register, and in trying to make the register much

more credible than the register with which we conducted the 2011

elections. I want to remind us that before the Anambra election, the

Commission met with Chairmen and Secretaries of political parties. All

registered political parties came along with Chairmen and Secretaries of

Anambra State branch of their parties. We briefed them adequately about

the improvement we have made to the register. We told them how the

number of registered voters in Anambra State had come down from about

1.8 million to about 1.7 million, because we did our best to eliminate

all multiple registrations. We also told them about the effort we are

making before the 2015 General Elections to ensure that, nationwide,

“addendum register” is eliminated in the conduct of elections. And we

briefed them about the effort we are making to ensure that when the

Anambra State governorship election was conducted, there would be no use

of the addendum register.

We briefed them about how in Anambra State before the governorship

election, we were going to do continuous voter registration, with the

main purpose of updating the register by allowing those who had become

18 years since the last registration to be put on the register. And we

also informed them how we were going to use the continuous voters

registration exercise to address the problem of addendum register. For

example, we briefed them about how anybody who is not on the electronic

register and who, therefore, voted during the 2011 Elections with their

names in the addendum register should use the opportunity of the

continuous voter registration to have their names captured and put on

the electronic register. Before we did the continuous voter

registration, we undertook massive publicity in Anambra State. We even

displayed printed copies of the electronic register that was used in the

2011 Elections so that people could see if their names were not on that

register and, if not, they could use the opportunity of the continuous

voter registration to have their names and details captured and put on

the register.

From our own assessment of these allegations of disenfranchisement, a

substantial majority if not all of those that were said to have gone to

polling units with their voter cards and did not find their names on

the register – in all likelihood, a substantial or overwhelming majority

of them, if not all of them – must be either people who have done

multiple registration, or were people who did not take advantage of the

continuous voter registration to have their names placed on the

electronic register.

The challenge is for political parties to provide evidence that there

were actually people who were deliberately excluded from the register –

that is, people outside of the list of those who had done multiple

registration and those who are on the addendum register. These were

people who were a priori not on the electronic register. No

evidence of this has been provided to us by any of the political

parties. Therefore, the allegations of disenfranchisement cannot be used

as sufficient reason to cancel the entire election.

There were complaints about a candidate or some other notable

Nigerians who had gone to the polling units and had their voter cards,

but they claimed to have been disenfranchised and were not allowed to

vote. I need to explain this.

The Electoral Act is very clear, and our guidelines are also very

clear, that if you present yourself as a voter in a polling unit, you

must first of all present your voter card; and then your name will be

checked in the register. If your name is not on the register, you will

not be allowed to vote. Our officials were trained in this, and they

were clearly complying with the training manual and the legal provisions

by ensuring that only those people whose names were found on the

register were allowed to vote. We have done some checking, and I can

tell you that in all likelihood – some we have, indeed, established –

any person who went to a polling unit and did not find his/her name on

the electronic register is very likely to have either done multiple

registration, or did not take advantage of the continuous voters’

registration to have their details captured and placed on the electronic

register.

I can speak more categorically about the candidate who said he went

to the polling unit and was not allowed to vote, whereas he voted in

2011. Our investigation showed that this person was on the manual

register, but not on the electronic register. Since 2011, it was the

manual register that was used to compile the addendum register; and

there is evidence of ticking on that manual register. In all likelihood,

it was with reference to the manual register that he, and perhaps many

others, were allowed to vote in April 2011. But we were not using the

addendum register in the governorship election that took place; we were

using only the electronic register. In all likelihood, that candidate

and many others that were mentioned did not utilize the opportunity of

the continuous voter registration to have their details captured and to

be placed on the electronic register. We did our best: we publicized

what people could do and, if people did not use the opportunity, it is

regrettable. This is the explanation of what happened in that

particular case.

Lessons from Anambra Election

As I said earlier, we recognize that the election we conducted in

Anambra State was neither perfect nor the best election we ever

conducted, or what we had wished. But we are satisfied that the conduct

of the election in spite of the challenges was free, fair and was

peaceful; and that the evidence provided to us was insignificant and did

not warrant total cancellation of the result. The decision of the

Returning Officer, in our view, on the need to have a supplementary

election is correct and we will abide by it.

I want to urge all stakeholders to cooperate and join hands with us

to ensure that the election in Anambra State is concluded and a return

is made. We have promised Nigerians that we as a Commission are

non-partisan and we will not collaborate with anybody to undermine the

electoral process; that if anybody does anything that is capable of

undermining the electoral process, we have the capacity to identify them

and once they are identified, we should be able to ensure that they

answer to the full requirement of the law.

It is regrettable that in Idemili North local government, we

identified the actions or inaction of our Electoral Officer as a major

obstacle to successful conduct of the election in that area, and the

enormous problem that arose with regard to the election. We have handed

over this Electoral Officer to security agencies for investigation, and

subsequent arraignment and prosecution. The police are already

investigating the matter and, obviously, the matter will be handled

appropriately.

I want to assure you that we are also undertaking internal

administrative inquiry on the lapses that have been identified, which as

we have said do not warrant total cancellation of the results of the

election. We are investigating the lapses and if we find any of our

staff culpable, they will have to answer for it. Obviously, as a

Commission, we are determined to keep on improving and we will ensure

that 2015 is much better than 2011 elections.

I regret to say that in spite of our best intentions, as human

beings, sometimes we get disappointed. As much as Nigerians were

disappointed with the outcome of the Anambra election, we also as a

Commission are disappointed. We wanted it to be the best, it has turned

out not to be the best. There were lapses, and we will ensure that all

these are investigated, the people responsible identified and

appropriate measures taken to rectify the situation as we move towards

other elections.

Saturday, 30 November 2013

Thursday, 28 November 2013

Deadlock, Confusion Greet APC, nPDP Merger As Kawu Baraje Faction Denies Signing MoU, Threatens To Return To PDP

Signs emerged last night that all may not be well with the much touted merger between the All Progressive Congress (APC) and the Kawu Baraje led faction of the People Democratic Party popularly knows as nPDP with the denial by the nPDP that they did not merge with the APC.

It declared yesterday that “what happened on Tuesday was merely "a declaration of intent to merge”.

The New PDP also gave indication that they might still return to the PDP if the party structures were returned to the governors of Adamawa, Kano and Rivers.

The Baraje faction stated that if their demands were still met, they would stop the Memorandum of Understanding, MoU, they wanted to sign with the APC on Tuesday.

Speaking on the Tuesday declaration by leaders of the New PDP and the APC, the publicity chief of the party, Chief Chukwemeka Eze, said the event at Kano Governor’s Lodge was misrepresented, clarifying that the parties had not signed any memorandum of understanding.

Eze said the parties in the alliance had just set up a committee to work on the conditions of the merger and that the report of the committee was to be submitted to the steering committee on Tuesday.

“It is only after we have signed the MoU that you can say we have merged. You guys should have asked us to list conditions of the merger. Can we merge without conditions?”

Eze explained that the chairman of the New PDP’s first phrase was that “We have agreed to work together but it was Chief Bisi Akande who insisted on the use of the word merger.

“I want to tell you that the matter is not concluded. We have to share positions. We have to agree on what will go to them and what will go to us. That is what the committee is still working on and nobody has signed the MoU.”

Asked whether the New PDP would attend the peace meeting called by President Goodluck Jonathan on Sunday, Eze said the New PDP would attend and that “all options are still on the table.”

“If the President agrees to our conditions, if we have agreements on issues that created the crisis, then we will not sign the MoU on Tuesday. So, from now till Tuesday, anything is still possible.

“If we meet on Sunday and our conditions are attended to, then the merger won’t go ahead. If Governor Amaechi is recognised as NGF chair, if the structures are returned to the governors of Adamawa, Kano and Rivers, then our leaders will look back and stop signing the MoU,” he said.

A few hours later, Eze sent a text message to refute his earlier statement that no MoU has been signed.

The letter that embarrassed me

I got a heartbreaking note yesterday, from a lady I have never met, who was a beneficiary of the 2011 round of scholarships.

I knew Godwin a long time ago. He was a brilliant and fearless

journalist, and active pro-democracy voice during the darkest days of

military dictatorship. Tragically he died in 2006, shot by unknown

gunmen on his way home from the office.Back then, all I could do was to help his family in the best way I could, by including his daughter in that year’s scholarship list for her postgraduate studies in Scotland. Back then I was mostly focused on helping young Nigerians go to study abroad, because we were all on the edge of exile anyway, and we thought it was best to send young people out to go see how freedom and democracy works, so they could come home and help make the country better.

I can vaguely remember one of my close staff and friend talking about Godwin’s other daughter applying for a scholarship in 2011, but because the scholarships were awarded on merit, all I remember was asking “Is she qualified”. I didn’t know she had been awarded the scholarship by the office. Not until yesterday.

My son sent me this note written by Godwin’s daughter, Ruona, and I was really touched by it. For very many reasons I cannot put down in words. I have given thousands of scholarships over the years, and read many “Thank You” notes, but this one stands out – not only because it thoroughly embarrassed me as Ruona intended, but because she has in her own decided to pay that gratitude into the lives of others by offering free journalism t

Police, Soldiers Stop Tinubu, Buhari, Others at INEC Office (PHOTOS)

Soldiers,

riot policemen and other security agencies confronted the leaders of

the All Progressives Congress (APC) during their march to the

headquarters of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) in

Abuja on November 28, 2013, Thursday.

After

a strategic meeting in the APC’s new secretariat in Wuse 2, the Federal

Capital Territory, which lasted about three hours, the party leaders

took to the streets and embarked on a procession to INEC’s office in

Maitama District.

The

protesters however met a stiff resistance from stern-looking security

operatives comprising the police, soldiers, SSS and Nigerian Security

and Civil Defence Corps.

An

armoured personnel carrier, marked NPF 6359 C, measuring about 40-feet

long, was used to barricade the entrance to the commission’s office,

while the driver of the truck and police officers were pelted with

sachets of water by the APC youths.

In

their separate speeches, the APC national Chairman, Chief Bisi Akande;

National Leader of the party and former governor of Lagos State, Asiwaju

Bola Tinubu; former chairman of ANPP, Dr. Ogbonnaya Onu; and ex-Head of

State, Maj.-Gen. Muhammadu Buhari (Rtd.), called for the sacking of

INEC Chairman, Prof. Attahiru Jega, with immediate effect for his

handling of the Anambra State governorship poll and the recent Delta

State Senatorial by-election.

See more photos below:

READ MORE: http://news.naij.com/53144.html

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

SHARIA POLICE SMASHES 240000 BOTTLES OF BEER IN KANO

Police enforcing Islamic law in the city of Kano publicly destroyed some 240,000 bottles of beer on Wednesday, the latest move in a wider crackdown on behaviour deemed “immoral” in the area.

The banned booze had been confiscated from trucks coming into the city in recent weeks, said officials from the Hisbah, the patrol tasked with enforcing the strict Islamic law, known as sharia.

- See more at: http://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/11/sharia-police-smash-240000-bottles-beer-kano/#sthash.DSDH3qln.dpuf

Kano’s Hisbah chief Aminu Daurawa said at the bottle-breaking ceremony he had “the ardent hope this will bring an end to the consumption of such prohibited substances”.

A large bulldozer smashed the bottles to shouts of “Allahu Ahkbar” (God is Great) from supporters outside the Hisbah headquarters in Kano, the largest city in Nigeria’s mainly Muslim north.

Kegs containing more than 8,000 litres of a local alcoholic brew called “burukutu” and 320,000 cigarettes were also destroyed.

“We hope this measure will help restore the tarnished image of Kano,” said Daurawa.

Since September, the Hisbah have launched sweeping crackdowns and made hundreds of arrests in Kano following a state-government directive to cleanse the commercial hub of so-called “immoral” practices.

The 9,000-strong moral police force works alongside the civilian police but also has other duties, including community development work and dispute resolution.

Sharia was reintroduced across northern Nigeria in 2001, but the code has been unevenly applied.

Alcohol is typically easy to find in Kano, including at hotels and bars in neighbourhoods like Sabon Gari, inhabited by the city’s sizeable Christian minority.

But the Hisbah boss vowed that this was set to change.

“We hereby send warning to unrepentant offenders that Hisbah personnel will soon embark on an operation into every nook and corner of (Kano) state to put an end to the sale and consumption of alcohol and all other intoxicants,” Daurawa said.

Tuesday, 26 November 2013

WE ARE NOT DISTUBED

The ruling Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) said yesterday it was not perturbed by the defection of five of its governors.

In what many see as a panic measure, the

party said President Goodluck Jonathan had agreed to meet with the

aggrieved governors on Sunday.

Before yesterday, Jonathan and the

leadership of the PDP were indecisive on the decision to meet with the

aggrieved members to resolve the protracted crisis in the party.

In a statement by its National Publicity

Secretary, Chief Olisa Metuh, the ruling party said: “We wish to state

categorically that the PDP remains unperturbed as we are now rid of

detractors and distractions. We urge all our members nationwide to

remain focused and close ranks, now that agents of distraction have

finally left our ranks.

“We wish to use this opportunity to

remind all PDP members that the peace process initiated by President

Goodluck Jonathan is still on course and we wish to thank him for his

patience, humility and spirit of accommodation. The meeting between the

President and aggrieved members shall hold on Sunday, December 01, 2013.

“We recognise the rights of freedom of

association for all Nigerians and declare that it is within the rights

of any Nigerian citizen to associate with anybody he/she deems fit.

“By this open declaration today, those

individuals have unveiled their true intent, which most Nigerians

suspected ab initio. They have chosen to abandon a broad based national

platform and embraced a narrow group of ethnic and religious bigots

whose main intention is to unleash a state of anarchy on Nigeria.”

Ex-militant, Asari-Dokubo arrested in Cotonou

A Former Niger Delta militant, Mujahid Asari-Dokubo, was on Tuesday arrested in Cotonou, capital of Benin Republic.

It was learnt that the ex-militant was arrested at about 1.00pm by the Benin Republic’s police.

A statement by his lawyer, Festus Keyamo

confirmed the arrest, saying Asari-Dokubo was picked up around the

Lubeleyi roundabout and taken to “an unknown destination.”

Keyamo, in the statement on Tuesday,

argued that Asari-Dokubo was not arrested for running any illegitimate

business in the country.

The lawyer noted that the ex-militant

had been residing partly in Benin Republic for many years, adding that

Asari-Dokubo owns property in Cotonou.

It was gathered that the ex-militant

reportedly opened a private university – King Amachree African

University, in Benin Republic.

The university is preparing to start degree-awarding programmes in 2014.

The statement reads in part, “Today,

Tuesday, November 26, 2013, my friend and client, Alhaji Mujahid

Dokubo-Asari, was arrested in Cotonou, Benin Republic, around the hours

of 1pm and 2pm by the country’s gendarmes (police).

“He was picked up around the Lubeleyi

roundabout and taken to an unknown destination. In fact, he owns houses,

schools and an academy in that country. All these places have been

searched as of this evening and nothing incriminating was found.”

Keyamo expressed the conviction that

“Dokubo’s arrest and detention are a ploy by certain forces in Nigeria

in an unholy alliance with the Beninoise government to keep him away as

2015 approaches.

“We call on the Nigerian government to

immediately intervene and ensure that no harm befalls Alhaji

Dokubo-Asari and to use all diplomatic means to secure his immediate

release and safe return to Nigeria.”

SOURCE:www.punchng.com

Monday, 25 November 2013

ASUU CONDITION TO END STRIKE

VARSITY teachers have agreed to suspend their five months old strike, The Nation learnt yesterday.

The Academic Staff Union of Universities

(ASUU) has given three conditions to be tabled before President Goodluck

Jonathan today. If the terms are acceptable to the Federal Government,

the union will call off the strike.

The ASUU leadership has banned its local

chapters and zonal chairmen from talking to the media until after the

session with the President.

ASUU President Dr. Nasir Issa Fagge and other leaders of the union were being expected in Abuja last night.

According to a source, who was part of

the ASUU session at Mambayya House in Kano, the conditions are:

•commitment from the President that any review or reconsideration or

renegotiation of the 2009 Agreement will not substantially affect the

pact which is the cause of the ongoing strike;

•immediate payment of all outstanding salary arrears and allowances of varsity teachers without victimization; and

•a written commitment from the President

that the Federal Government will commit N225billion annually to the

funding of universities for the next four years.

There is a fourth condition, which is

said to be “personal” to ASUU, bordering on the need to be wary of

gradual loss of public sympathy.

The union leaders were said to have

recognised public goodwill for the strike and the need to avert any

action that could erode such confidence.

The source said: “Our leaders are meeting

with the President on Monday to table these conditions. Once the

President accepts these three terms, the strike will be called off.

“In principle, members voted about 60-40

per cent to call off the strike, but they added a caveat – that

ICC Declares Conflict in N’Eastern Nigeria Civil War

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has determined that the conflict between Boko Haram insurgents and the security forces in northern-eastern Nigerian is a civil war.

In a report released at the weekend from the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) of the ICC titled: “Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2013”, which focused on conflicts, genocide and crimes against humanity in 10 countries, including Nigeria, ICC said after a careful review of the situation, the violence in Nigeria qualified as an armed conflict of non-international character.

Under the Geneva Conventions, a "non-international armed conflict" (NIAC) is the technical name for a civil war. This brings the ICC into line with a similar determination made by the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) earlier this year.

The determination that the situation is a NIAC also means that the norms of international humanitarian law, including in particular, Article 3 Under the Geneva Conventions, are formally deemed to be applicable to the theatre of conflict.

The prosecutor’s report stated: “The required level of intensity and the level of organisation of parties to the conflict necessary for the violence to be qualified as an armed conflict of non-international character ap

Sunday, 24 November 2013

Syria’s Bloodshed Engulfs Beirut

The

streets of Hamra, a busy Beirut district, are packed on Thursday

nights. It’s the start of the Middle Eastern weekend, the time when

friends meet at the cafes and coffee shops to celebrate the end of the

workweek.

The red and white Christmas lights – even though this is not a predominantly Christian neighborhood – have just gone up.

Weekends are popular in Beirut. Hairdressers are full.

Music and laughter blare out of car windows. Restaurants, despite an

economic crisis, are packed.

But after Tuesday’s twin suicide bombings that ripped

through concrete walls of the Iranian Embassy in the southern suburbs,

killing 23 people, including an Iranian diplomat, and wounding 146,

there is a clear underlying tension.

Suicide bombings in this part of the world usually trigger a

retaliation. A day after the attacks, the Iranian-backed Hezbollah –

the Shiite “Party of God” – warned that more bombs similar to the

suicide blasts could be set off.

“But we’re Lebanese. No one is going to stay home because

of the bombs,” said Hosam, who owns and runs a small business here. Born

at the start of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, Hosam and his family

have lived through sectarian strife before.

“The war went on until 1990, so my entire childhood and

teenage years were about seeing people killed,” he said. “It was a

terrible time. You see downtown Beirut now? It’s beautiful. But I

remember the war. The Green Line, [which divided East and West Beirut,]

the bullets, and dogs eating dead bodies on the streets.”

Hosam does not want his two small children to experience

the bomb-strewn, bloody childhood he had to endure. And yet he feels

that with the escalating Sunni-Shiite tensions and the spillover from

neighboring Syria’s war, his entire family will soon be affected.

The bombings were the first on an Iranian target, and the

most serious in the southern suburbs, since the 32-month conflict in

Syria began. The embassy is nestled deep in the heart of the fiefdom of

Hezbollah – whose fighters are currently backing the regime of President

Bashar al-Assad in the civil war in neighboring Syria.

Within hours, the al Qaeda–backed Abdullah Azzam brigade

was boasting on Twitter, taking full credit for the attack. Sheikh

Sirajuddin Zurayqat said attacks on Lebanon would continue unless

Hezbollah fighters pull out of Syria.

The Sunni jihadist group the Azzam brigade is based in

Lebanon but has ties to Saudi. The Saudis – along with other Sunni

groups backing the Syrian rebels – are increasingly agitated by the

assistance Hezbollah and Iran are giving to Assad. The rebels just lost

another strategic town, Qara, north of Damascus, over the weekend and

are feeling their losses acutely.

A year ago, Lebanese people did not think they could be

pulled into the troubles of their neighbor. “We’ve seen too much war. We

will never experience that again,” said Maria, a Christian teacher in

Tripoli in northern Lebanon, when asked whether war could return to her

country.

But this week, the sight of charred bodies, broken bones

and families searching for loved ones near the bombing site triggers a

bitter memory of the civil war. That conflict left deep scars. It broke

spirits, destroyed cities, scattered families, and sent thousands of

Lebanese into exile.

“Lebanon is being dragged into the Syrian conflict. The

spillover is unmistakable,” said Professor Hilal Khashan from the

American University in Beirut.

Khashan believes the perpetrators were clearly “jihadists

from Syria who crossed the border.” He said this is the first suicide

bombing in Lebanon since 1983, when, almost exactly 30 years ago, two

attacks targeted the U.S. Marines and the French military headquarters,

killing 299 American and French servicemen.

Aero Contractor reportedly changes name to Nigerian Eagle

According to new reports, Aero Contractors, partly owned by the Ibru family

has changed its name to

Nigerian Eagle, and will most likely be the official national carrier.

Thisday reports that the airline will be unveiled this Sunday as the nation's national carrier by

President Goodluck Jonathan on his return from the UK.

The Federal Government owns 60% stake in the airline"There will not be Aero Contractors anymore. It is now Nigerian Eagle and it will be launched on Sunday by Mr. President. You will not see Aero anymore after the launch of this airline”. Sources told Thisday on Wednesday,

HISTORICAL AGREEMENT

Iran has agreed to curb some of its nuclear activities in return for about $7bn (£4.3bn) in sanctions relief, after days of intense talks in Geneva.

US President Barack Obama welcomed the deal, saying it included "substantial limitations which will help prevent Iran from building a nuclear weapon".

Iran agreed to give better access to inspectors and halt some of its work on uranium enrichment.

President Hassan Rouhani said the deal recognised Iran's nuclear "rights".

But he repeated, in a nationwide broadcast, that his country would never seek a nuclear weapon.

Tehran denies repeated claims by Western governments that it is seeking to develop nuclear weapons. It insists it must be allowed to enrich uranium to use in power stations.

The first announcement of the most important agreement between

Iran and the West in more than a decade was made on Twitter. Shortly

before three in the morning in Geneva, the EU posted: "We have reached

agreement between the E3+3 and Iran." Minutes later, Iran's chief

negotiator, Mohammad Javad Zarif followed: "We have reached an

agreement."

The immediate origins of this deal date to 14 June 2013, when Hassan Rouhani was elected president of Iran. Mr Rouhani promised to end his country's repeated confrontations with the outside world, beginning with the argument over its nuclear programme.

To bring about a deal, Mr Rouhani pursued two key policies. Firstly, he secured the public backing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei for his diplomatic efforts. Secondly, the new president and his foreign minister broke precedent and pursued direct high-level contact with Iran's long time enemy, the US.

If there is to be a lasting nuclear agreement, it may spring from a reconciliation between these two countries.

The immediate origins of this deal date to 14 June 2013, when Hassan Rouhani was elected president of Iran. Mr Rouhani promised to end his country's repeated confrontations with the outside world, beginning with the argument over its nuclear programme.

To bring about a deal, Mr Rouhani pursued two key policies. Firstly, he secured the public backing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei for his diplomatic efforts. Secondly, the new president and his foreign minister broke precedent and pursued direct high-level contact with Iran's long time enemy, the US.

If there is to be a lasting nuclear agreement, it may spring from a reconciliation between these two countries.

The deal comes just months after

Iran elected Mr Rouhani - regarded as a relative moderate - as its new

president, in place of the hard-line Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

It has also been backed by Iran's Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.After four days of negotiations, representatives of the so-called P5+1 group of nations - the US, the UK, Russia, China, France and Germany - reached an agreement with Iran in the early hours of Sunday.

The specifics of the deal have yet to be released, but negotiators indicated the broad outlines:

- Iran will stop enriching uranium beyond 5%, the level at which it can be used for weapons research, and reduce its stockpile of uranium enriched beyond this point

- Iran will give greater access to inspectors including daily access at Natanz and Fordo nuclear sites

- In return, there will be no new nuclear-related sanctions for six months

- Iran will also receive sanctions relief worth about $7bn (£4.3bn) on sectors including precious metals

But the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told his cabinet it was a "historic mistake" and that his country reserved the right to defend itself.

"Today the world became a much more dangerous place because the most dangerous regime in the world made a significant step in obtaining the most dangerous weapons in the world," he said.

The Israeli comments came as it was revealed that the US and Iran had held a series of face-to-face talks over the past year that were kept secret even from their allies.

Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said it was an opportunity for the "removal of any doubts about the exclusively peaceful nature of Iran's nuclear programme".

President Hassan Rouhani said the deal recognised Iran's nuclear "rights"

"We believe that the current agreement, the current plan of action as we call it, in two distinct places has a very clear reference to the fact that Iranian enrichment programme will continue and will be a part of any agreement, now and in the future," he said.

The US denied any such right had been conceded, while UK Foreign Secretary William Hague said the agreement was "good news for the whole world".

'Significant agreement' The US state department gave more details of the deal, insisting that most sanctions would remain in place.

Restrictions on Iran's petrochemical exports and some other sectors would be suspended, bringing in $1.5bn in revenue.

Obama: "Agreed to provide Iran with modest relief"

This deal may be the most significant agreement between the world powers and Iran for a decade, says the BBC's James Reynolds in Geneva.

Negotiators had been working since Wednesday to reach an agreement that was acceptable to both sides.

As hopes of a deal grew stronger, foreign ministers of the P5+1 joined them in Geneva.

But it only became clear that a breakthrough had been made in Geneva shortly before 03:00 local time (02:00 GMT) on Sunday

SOURCE: www.bbc.co.uk

Friday, 22 November 2013

Nov. 22, 1963, a date Dallas will never truly get beyond

Fifty years is a relative blip on the grand timeline, barely a rounding error between your genesis point and the end of life as we know it. Yet in human terms, 50 years is longer than many life spans, past and present.

In Dallas terms, 50 years is five decades of exploration, examination and grinding introspection about what happened, and why, on Nov. 22, 1963, in Dealey Plaza.

John F. Kennedy’s slaying was a seminal event in our city’s history, encapsulating too much that came before and influencing much that would follow, and here we are. We have considered it, studied it, reflected and grieved.

It’s tempting to acquiesce after all these years, to step away from the pain and sadness and horror of a president’s murder on our streets, and say, finally: “Enough. We are past that now.”

That many of us have obsessed about this single moment for so long says something. Dallas today bears little resemblance to 1963 Dallas. Divisions and demarcations, fading away by the decade, were stark. Today’s politics may have troubling elements, but they are a shallow dive compared with the dangerous extremism then.

“City of Hate” was not meant as an irony. It wasn’t an entire city, far from it, but certainly a part. With 50 years of hindsight, calling Dallas the city that killed Kennedy was neither fair nor accurate, given the lack of evidence that anyone other than a troubled loner was involved. Yet the allegation wasn’t that Dallas pulled the trigger, necessarily, but whether such a heinous crime could have happened anywhere else.

In truth, few 1963 U.S. cities would bear up well under scrutiny from 2013 eyes. America changed, and Dallas changed with it — more than many cities, perhaps, because it had a longer way to go. On balance, this has been a positive drawn from our introspection.

Another is the openness of our rumination. The events today in Dealey Plaza, remembering the 50th anniversary of a president’s death, are years in the making. City leaders, elected and unelected, have weighed competing priorities to find an appropriate ceremony that, importantly, strikes the right tone.

Despite what some outsiders might argue, Dallas has not shied away from hard questions. This, too, says something important about our city, even if fewer than 10 percent of its residents today were here on Nov. 22, 1963. This story, this event, belongs to all of us.

Which is why Dallas will resist the temptation to simply move beyond this moment, if that means shoving it onto some forgotten bookshelf.

A president was killed here for reasons that died with his killer. It does us no good to pretend this didn’t happen 50 years ago. From this terrible day and all the ones that follow, we will keep learning about ourselves and our city.

SOURCE: http://www.dallasnews.com

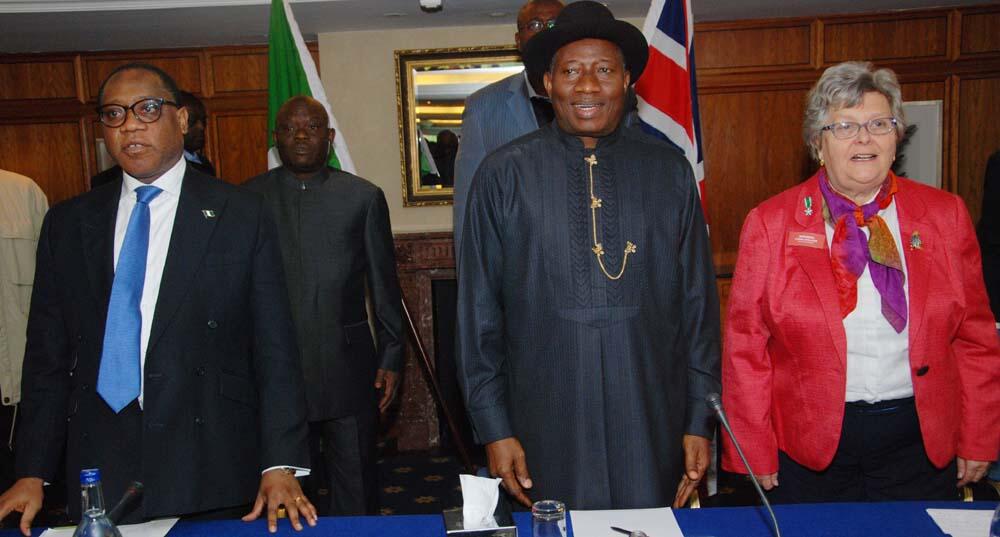

AT HIIC MEETING IN LONDON, PRESIDENT JONATHAN SAYS FG WILL CONTINUE TO IMPLEMENT BOLD AND COURAGEOUS REFORMS

STATE HOUSE PRESS RELEASE

AT HIIC MEETING IN LONDON, PRESIDENT JONATHAN SAYS FG WILL CONTINUE TO IMPLEMENT BOLD AND COURAGEOUS REFORMS

President Goodluck Jonathan addressed the ongoing meeting of Nigeria's Honourary International Investors' Council Friday in London having made a speedy recovery from the indisposition he experienced yesterday.

After apologising to the council members for his absence yesterday, President Jonathan said that his administration has attained significant momentum on the drive to attract new investors into the country and will continue to encourage existing investors within the country to expand.

"In 2014, we must not lose this momentum, but rather broaden our interventions to address other difficult issues like the high cost of financing in the country, and the dearth of adequate skills.

"This 15th meeting builds on the last conversation we had in Abuja and begins to address the fundamental issues constraining competitiveness and investment in Nigeria. Competitiveness ultimately drives profitability, which is what investors are seeking worldwide.

"To be competitive, we must address long standing issues, and introduce bold and courageous reforms, regardless of short term political pressures. This is why my government has remained steadfast in making Nigeria the preferred location for investors to do business, because it is our only pathway to create jobs, generate wealth, and guarantee our security.

"In building a truly competitive environment for business, we are addressing the fundamental issues such as internal security and power supply head-on. For the first time in Nigeria's 53 year history, we have successfully privatized the electric power industry.

"We are bringing capital, technology, and operational excellence into the sector. As a result, 11 distribution companies, and four (4) generation companies have been privatized, realising over US$3 billion for Government. For Council’s information the assets were finally handed over on 1st November, 2013.

"I am delighted to inform you that investors are responding positively to the opportunities in the sector and we expect to see significant investments in the sector and across the value chain going forward. Ladies and Gentlemen, resolving the power sector alone, completely changes the paradigm on doing business in Nigeria, and we are satisfied with the progress made.

"Equally, although challenges remain, we are investing in the requisite security infrastructure and intelligence network that will enable us deal more effectively with the new threats we face which can and do hamper investor confidence in our economy.

"In ensuring that the environment is suitable for investment, we will also continue to intensify the fight against corruption. We are indeed happy that the private sector has begun complementing our strong desire to tackle all forms of rent seeking tendencies. The “Clean Business Nigeria Today” initiative coming from the meetings of the Council is a very good example.

"I also use this opportunity to inform Council that Nigeria will be hosting the World Economic Forum on Africa, between the 7th and 9thof May 2014.

"Our hosting this event is yet again a strong sign of Nigeria’s central economic and political role on the continent. The forthcoming World Economic Forum will be used to shape matters of inclusive growth on the continent, and I invite all members of Council to join us in Abuja in May 2014," President Jonathan told members of the council.

The President participated in a discussion of the presentation by the Minister of Communications Technology on the development of ICT infrastructure in Nigeria.

He was also briefed on the council's deliberations yesterday on measures to secure additional sources of financing for essential development projects in Nigeria.

Baroness Lynda Chalker who coordinates the council, told President Jonathan that its members felt much more positive about the opening up of investment opportunities in Nigeria.

She said that the attendance at the ongoing meeting of the Council was the highest ever in its history and that its members were very excited about the emerging potentials of the Nigerian economy.

Reuben Abati

Special Adviser to the President

(Media & Publicity)

November 22, 2013

AT HIIC MEETING IN LONDON, PRESIDENT JONATHAN SAYS FG WILL CONTINUE TO IMPLEMENT BOLD AND COURAGEOUS REFORMS

President Goodluck Jonathan addressed the ongoing meeting of Nigeria's Honourary International Investors' Council Friday in London having made a speedy recovery from the indisposition he experienced yesterday.

After apologising to the council members for his absence yesterday, President Jonathan said that his administration has attained significant momentum on the drive to attract new investors into the country and will continue to encourage existing investors within the country to expand.

"In 2014, we must not lose this momentum, but rather broaden our interventions to address other difficult issues like the high cost of financing in the country, and the dearth of adequate skills.

"This 15th meeting builds on the last conversation we had in Abuja and begins to address the fundamental issues constraining competitiveness and investment in Nigeria. Competitiveness ultimately drives profitability, which is what investors are seeking worldwide.

"To be competitive, we must address long standing issues, and introduce bold and courageous reforms, regardless of short term political pressures. This is why my government has remained steadfast in making Nigeria the preferred location for investors to do business, because it is our only pathway to create jobs, generate wealth, and guarantee our security.

"In building a truly competitive environment for business, we are addressing the fundamental issues such as internal security and power supply head-on. For the first time in Nigeria's 53 year history, we have successfully privatized the electric power industry.

"We are bringing capital, technology, and operational excellence into the sector. As a result, 11 distribution companies, and four (4) generation companies have been privatized, realising over US$3 billion for Government. For Council’s information the assets were finally handed over on 1st November, 2013.

"I am delighted to inform you that investors are responding positively to the opportunities in the sector and we expect to see significant investments in the sector and across the value chain going forward. Ladies and Gentlemen, resolving the power sector alone, completely changes the paradigm on doing business in Nigeria, and we are satisfied with the progress made.

"Equally, although challenges remain, we are investing in the requisite security infrastructure and intelligence network that will enable us deal more effectively with the new threats we face which can and do hamper investor confidence in our economy.

"In ensuring that the environment is suitable for investment, we will also continue to intensify the fight against corruption. We are indeed happy that the private sector has begun complementing our strong desire to tackle all forms of rent seeking tendencies. The “Clean Business Nigeria Today” initiative coming from the meetings of the Council is a very good example.

"I also use this opportunity to inform Council that Nigeria will be hosting the World Economic Forum on Africa, between the 7th and 9thof May 2014.

"Our hosting this event is yet again a strong sign of Nigeria’s central economic and political role on the continent. The forthcoming World Economic Forum will be used to shape matters of inclusive growth on the continent, and I invite all members of Council to join us in Abuja in May 2014," President Jonathan told members of the council.

The President participated in a discussion of the presentation by the Minister of Communications Technology on the development of ICT infrastructure in Nigeria.

He was also briefed on the council's deliberations yesterday on measures to secure additional sources of financing for essential development projects in Nigeria.

Baroness Lynda Chalker who coordinates the council, told President Jonathan that its members felt much more positive about the opening up of investment opportunities in Nigeria.

She said that the attendance at the ongoing meeting of the Council was the highest ever in its history and that its members were very excited about the emerging potentials of the Nigerian economy.

Reuben Abati

Special Adviser to the President

(Media & Publicity)

November 22, 2013

President Jonathan and Baroness Lynda Chalker earlier this morning at the HICC Meeting in London.

PRESIDENT JONATHAN RECOVERS FROM ILLNESS. PRESIDES OVER HIC MEETING IN LONDON

Reuben Abati

President Jonathan recovers

from indisposition, he is presiding over the HIIC meeting in London

right now. Will deliver his address shortly.

One more pic from HIIC meeting in London today.

right now. Will deliver his address shortly.

Drivers of illegal tinted vehicles jail or N50,000 fine

Senate yesterday approved a legislation prescribing six months jail for anyone caught driving vehicles with tinted glass illegal. The offender may pay a N50,000 fine in lieu of imprisonment. This is contained in the Bill for an Act to amend the Motor Vehicle (Prohibition of tinted glass) Act aimed at checking indiscriminate use of tinted glass.

The new legislation seeks essentially, “to amend the extant law in order to check indiscriminate use of tinted glass vehicles which beat security checks and carry out nefarious activities.”

The amendment was done following the spate of reactions from Nigerians on the recent announcement by the police of their intention to arrest and prosecute those driving vehicles with tinted glass .

Senate acknowledged that the police were not trying to introduce a new law, but was merely trying to enforce an already existing regulation 66 (2) of the National Traffic Regulations of 1997 and the Motor Vehicles (Prohibition of tinted glass) Act.

The bill, among other provisions, requests buyers of imported vehicles with tinted, shaded, coloured, darkened or treated glass to change them to transparent ones within 14 days from the date of arrival in Nigeria or date of purchase.

In the alternative, it demands that buyers of such vehicles should request for a permit for the use of such tinted glass vehicles from the Office of the Inspector-General of Police, anywhere in the country, within 90 days of importing the vehicle.

It is also an offence for anyone to procure tinted glass on vehicles brought into the country with transparent glass, otherwise than in accordance of the provisions of the Act.

An individual who bought a tinted glass vehicle without changing it to transparent glass within 14 days, according to the bill, shall be liable to N2, 000 fine or be jailed for six months, or to both.

The bill also said that an individual who failed to seek registration for permit shall upon conviction be liable to a fine of N50, 000 or to a six-month imprisonment or both.Deputy Senate President, Ike Ekweremadu, who chaired the session, commended his colleagues for passing the bill, noting that tinted glass vehicles were constituting security challenges and that their continued usage could cause accidents.

Thursday, 21 November 2013

Dressed in Classy Jacket, Messi Gets the European Golden Shoe for Scoring Most Goals in a Season.

The Argentina ace netted 46 times in La Liga as the Catalan giants

reclaimed their title back from Real Madrid and he was presented with

the trophy in Barcelona on Wednesday.

Messi, 26, also won the award following the 2009/10 season, when he scored 34 goals, and again after the 2011/12 campaign when he found the back of the net 50 times.

And a modest Messi said after being presented with the trophy by former Barca and Bulgaria forward Hristo Stoichkov, who was joint-winner in 1990: ‘I dedicate this award to my family, to the people who are there in the toughest times, and my team-mates.

‘I want to thank them because without them I wouldn’t have achieved anything. It’s a prize for the squad.’

Winners since 2006:

2006-07 Francesco Totti (AS Roma) 26 goals

2007-08 Cristiano Ronaldo (Manchester United) 31 goals

2008-09 Diego Forlan (Atletico Madrid) 32 goals

2009-10 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 34 goals

2010-11 Cristiano Ronaldo (Real Madrid) 40 goals

2011-12 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 50 goals

2012-13 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 46 goals

Messi, who is currently sidelined for eight weeks with a hamstring injury, is the only player to win the trophy three times.

Regarding his injury and the possibility of being back in action by 2014, Messi said: ‘I’m better, improving little by little, I’m nearly without any pain and starting to do little things.

‘I haven’t put a return date, if everything goes well this will be the date (first game of next year) to return, but we’ll see how the recovery goes. It will happen when it has to happen.’

Messi enjoyed a typically successful start to the season with eight goals in 11 Primera Divison appearances before tearing his hamstring against Real Betis earlier this month.

However, his chances of winning a fourth Golden Shoe this season will have been badly hit by that injury, with Ronaldo already having notched 16 times in La Liga this term, with two hat-tricks in his last three matches.

SOURCE:www.stargist.com

Messi, 26, also won the award following the 2009/10 season, when he scored 34 goals, and again after the 2011/12 campaign when he found the back of the net 50 times.

And a modest Messi said after being presented with the trophy by former Barca and Bulgaria forward Hristo Stoichkov, who was joint-winner in 1990: ‘I dedicate this award to my family, to the people who are there in the toughest times, and my team-mates.

‘I want to thank them because without them I wouldn’t have achieved anything. It’s a prize for the squad.’

Winners since 2006:

2006-07 Francesco Totti (AS Roma) 26 goals

2007-08 Cristiano Ronaldo (Manchester United) 31 goals

2008-09 Diego Forlan (Atletico Madrid) 32 goals

2009-10 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 34 goals

2010-11 Cristiano Ronaldo (Real Madrid) 40 goals

2011-12 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 50 goals

2012-13 Lionel Messi (Barcelona) 46 goals

Messi, who is currently sidelined for eight weeks with a hamstring injury, is the only player to win the trophy three times.

Regarding his injury and the possibility of being back in action by 2014, Messi said: ‘I’m better, improving little by little, I’m nearly without any pain and starting to do little things.

‘I haven’t put a return date, if everything goes well this will be the date (first game of next year) to return, but we’ll see how the recovery goes. It will happen when it has to happen.’

Messi enjoyed a typically successful start to the season with eight goals in 11 Primera Divison appearances before tearing his hamstring against Real Betis earlier this month.

However, his chances of winning a fourth Golden Shoe this season will have been badly hit by that injury, with Ronaldo already having notched 16 times in La Liga this term, with two hat-tricks in his last three matches.

SOURCE:www.stargist.com

Wednesday, 20 November 2013

Why John F. Kennedy's Legacy Endures 50 Years After His Assassination

NOVEMBER 22, 1963

It began like any other day, but that day and its aftermath soon became hard-wired into the American psyche, black and white images still tainted with emotion in the minds of millions of Americans. For most of those old enough to remember, it holds a prominent place in their memories—the day JFK died—and the day when a bullet tore through the fabric of 20th Century America.

The news came suddenly, without warning. Gunshots in Dallas shattered American complacency about their national superiority. Nesting within a warren of cardboard boxes, a lone gunman with a mail-order gun had attacked the elected leader of the world’s foremost democracy. As Americans rushed to get the latest news and later mourned the president’s death, many immediately drew comparisons with Abraham Lincoln’s murder. However, few Americans recalled Presidents James Garfield and William McKinley, who also lost their lives to gunfire and many Americans in 1963 may have expected Kennedy’s death to be similarly lost in American memory.

However, it has been fifty years since that sunny autumn day in Dallas, and yet, many Americans still mourn and still exhibit fascination with the youngest man ever elected president. Neither Garfield nor McKinley could claim such a lasting hold on the American imagination.

In Africa, does democracy improve your health? – By Eleanor Whitehead and Zoe Flood

Back in the 1990s, the Nobel-prize winning economist Amartya Sen famously wrote that “no famine has ever taken place in a functioning democracy”, coining an argument has shaped thinking across countless sectors – and none more so than healthcare. If governments face open criticism and are under pressure to win elections, we assume, they are incentivised to improve the health of their populations. Dictators are not.

“Democracy is correlated with improved health and healthcare access… Democracies have lower infant mortality rates than non-democracies, and the same holds true for life expectancy and maternal mortality,” Karen Grépin, assistant professor of global health policy at New York University, wrote in a 2013 paper. “Dictatorship, on the other hand, depresses public health provision.”

She argues that democracies entrench longer-term reforms than their dictatorial counterparts – often involving universal healthcare or health insurance schemes. “The effects of democracy are more than a short-term initiative, such as an immunisation programme, which don’t always have lasting effects,” she said in a telephone interview. “Democracy can bring larger-scale reforms that create new things or radically transform institutions.”

But does that theory hold water in Africa?

Ghana, one of the continent’s deepest democracies, is doing well. According to Gallup data, 75 percent of its population consider its elections to be honest, compared to a median of 41 percent over 19 sub-Saharan countries. Correspondingly, it was also one of the first countries in Africa to enact universal health coverage laws.

In 2003, roughly a decade after entering a multi-party democratic system, the west African country hiked VAT by 2.5 percent to fund a national health insurance programme. Voters who had been overstretched by the previous ‘cash-and-carry’ system happily swallowed the tax increases, and the scheme was so popular that when the government unexpectedly changed in 2008, it survived the transition.

The country still has a way to go to attain universal coverage. According to the National Health Insurance Authority, by the end of 2010 34 percent of the Ghanaian population actively subscribed to the scheme. But the institutions are now in place, laying the foundations for the future.

Similar schemes are being rolled out in other democracies like South Africa. But this isn’t a simple equation. There are plenty more multi-party systems which have failed to enact meaningful reform – think of the pitiful performance in Kenya, where the government changed earlier this year – while some more autocratic regimes are performing well.

“Several of the countries that are seen as the big success stories in public health are not very democratic,” argued Peter Berman, a health economist at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Take Rwanda. Led by Paul-Kagame’s decidedly authoritarian Rwandan Patriotic Front, the country is considered “not free” by Freedom House. In the run up to 2010 presidential elections Human Rights Watch alleged political repression and intimidation of opposition party members against the leadership. Yet the government has a strong developmental track record. “Rwanda started out with somebody who is autocratic, but who genuinely wants to see these indicators change,” Grépin said.

Over the last decade, Rwanda has registered some of the world’s steepest healthcare improvements. After the 1994 genocide – when national health facilities were destroyed and disease was running rampant – life expectancy stood at 30 years. Today, citizens live to an average of almost double that. Deaths from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria have each dropped by roughly 80 percent over the last 10 years, while maternal and child mortality rates have fallen by around 60 percent.

Part of its success stems from the fact that its healthcare services reach rural citizens. The leadership hands responsibility to local government and authorities and holds them accountable for their efficiency; and almost 50,000 community health workers have been trained to deploy services to marginal populations.

Like Ghana, Rwanda runs a universal health insurance scheme, though it has fared better in its roll out. Upwards of 90 percent of the population is covered by the community-based Mutuelles de Santé programme, which has more than halved average annual out-of-pocket health spending. “By decreasing the impact of catastrophic expenditure for health care we increase the access,” explained Agnes Binagwaho, minister of health, from her Kigali office.

The benefits of that programme are clear to see at the bustling Kimironko Health Centre, which is a 20-minute drive from central Kigali and deals with most of the suburb’s non-life threatening medical complaints. As dozens of men, women and children queue to hand over their health cards, a young nurse named Francine Nyiramugisha explains that “Ever since the Mutuelles de Santé was introduced, there has been a huge difference. You pay 3,000 RwF ($4.50) per year and then you get treatment.”

In the reception, thirty-year-old Margaret Yamuragiye, a slender sociology student who has been diagnosed with malaria, waits patiently for her prescription. “Before I got my Mutuelles card I would fear that I could not go to the clinic because it would be too expensive. Today if I have simple cough or flu, I come to the doctor, I don’t wait to see if it gets worse,” she said.

Nearby in Ethiopia, another autocratic regime registered by Freedom House as “not free” is also clocking significant health improvements. Like Rwanda, leaders in Addis Ababa have little time for political opposition, but are registering impressive developmental gains. “They’re not very democratic but they have the power and authority to allocate resources towards population health needs,” Harvard’s Berman said.

There’s no universal coverage scheme in Ethiopia, but government has opted to focus on deploying basic healthcare services across hard-to-reach rural areas. Starting from a pitifully low base, it has spent a decade training a network of around 40,000 extension workers to bring care to rural communities. Over ten years, the nation registered a more than 25 percent decline in HIV prevalence, according to a 2012 progress report. Under-five mortality has declined to 101 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2009/10, from 167 in 2001/2. Infant mortality halved in the same period.

Those examples should be evidence enough that the relationship between democracy and improved healthcare isn’t a simple one. “There are autocratic governments that care about the people and there are autocratic governments who don’t. There are democracies where politicians respond to a broad public demand, and then there are democracies where the politicians respond to narrower interest groups,” Berman said.

“There is no simple equation between democracy and caring about public health.”

SOURCE:www.africanarguments.org

FALLOUT OF ANAMBRA GUBERNATORIAL ELECTIONS

A

principal actor in the controversial Anambra governorship election of

November 16 has reportedly made sterling revelations to his

interrogators in Abuja.

Mr Okeke Chukwujekwu, the electoral

officer in charge of Idemili North local government area of Anambra

State, currently in police detention over his role in the electoral

saga, was said to have told his police investigators that he was “being

used and dumped”.

The chairman of the Independent National

Electoral Commission (INEC), Professor Attahiru Jega, had, in the heat

of the controversies generated by the flawed poll, admitted that the

“electoral officer” in Idemili North “messed up” and that he would be

handed over to the police for prosecution.

Chukwujekwu was moved to

Abuja on Sunday, just as INEC said it was conducting a probe into the

deliberate sabotage of the governorship election.

A top

official involved in the election confided in LEADERSHIP yesterday that

the arrested INEC official had made useful statements even as he was

apprehensive that top directors of INEC might be “implicated”.

“The

way this whole thing is going, it looks as if many heads will roll in

INEC because the young man has made useful statements and if what he

said is anything to rely upon, it then means that some big names in that

commission might fall with him.

“At first, he was trying to

rationalise his action in that local government area when he was

verbally quizzed before the intervention of the police; but, after some

time, especially at the point of his detention, he started to cooperate

but the cooperation is loaded because he has mentioned some top

officials of INEC, especially directors and a PDP chieftain, as those

who ‘put him in trouble’.

Friday, 15 November 2013

Multiple Registrations: Court Orders Documents Pasted at Obiano's Residence

A Federal High Court, Thursday in Abuja, ordered the service of court

documents (processes) on the governorship candidate of the All

Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) in tomorrow’s election, Chief Willie

Obiano.

The documents are in respect of a suit marked: FHC/ABJ/CS/712/2013 -

challenging Obiano's qualification for the election on the ground that

he possessed two voter's cards, having allegedly engaged in multiple

registrations.

Justice Ahmed Mohammed, after listening to the plaintiffs' lawyer,

Ifeanyi Nrialike, moved an ex-parte motion, granted leave to the

plaintiffs to effect substituted service of court processes on Obiano

outside jurisdiction.

The judge also ordered the plaintiffs - Ugochukwu Ikegwuonu and Kenneth

Moneke to, in effecting the substituted service, paste the processes on

the entrance or any other conspicuous parts of his residence at 1 Chief

Willie Obiano Street, Aguleri Otuocha, Anambra State.

Sued with Obiano is the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC).

Sued with Obiano is the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC).

The plaintiffs had contended that the voter's card Obiano tendered

before his party which allowed him to participate in the party's

screening exercise was not the same as the one he submitted to INEC and

therefore raised three questions for the court's determination, while

seeking five reliefs, including an order disqualifying Obiano from

contesting the election.

They also sought an order of mandatory injunction compelling INEC to strike out Obiano's name from its record as a candidate in the election.

They also sought an order of mandatory injunction compelling INEC to strike out Obiano's name from its record as a candidate in the election.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)